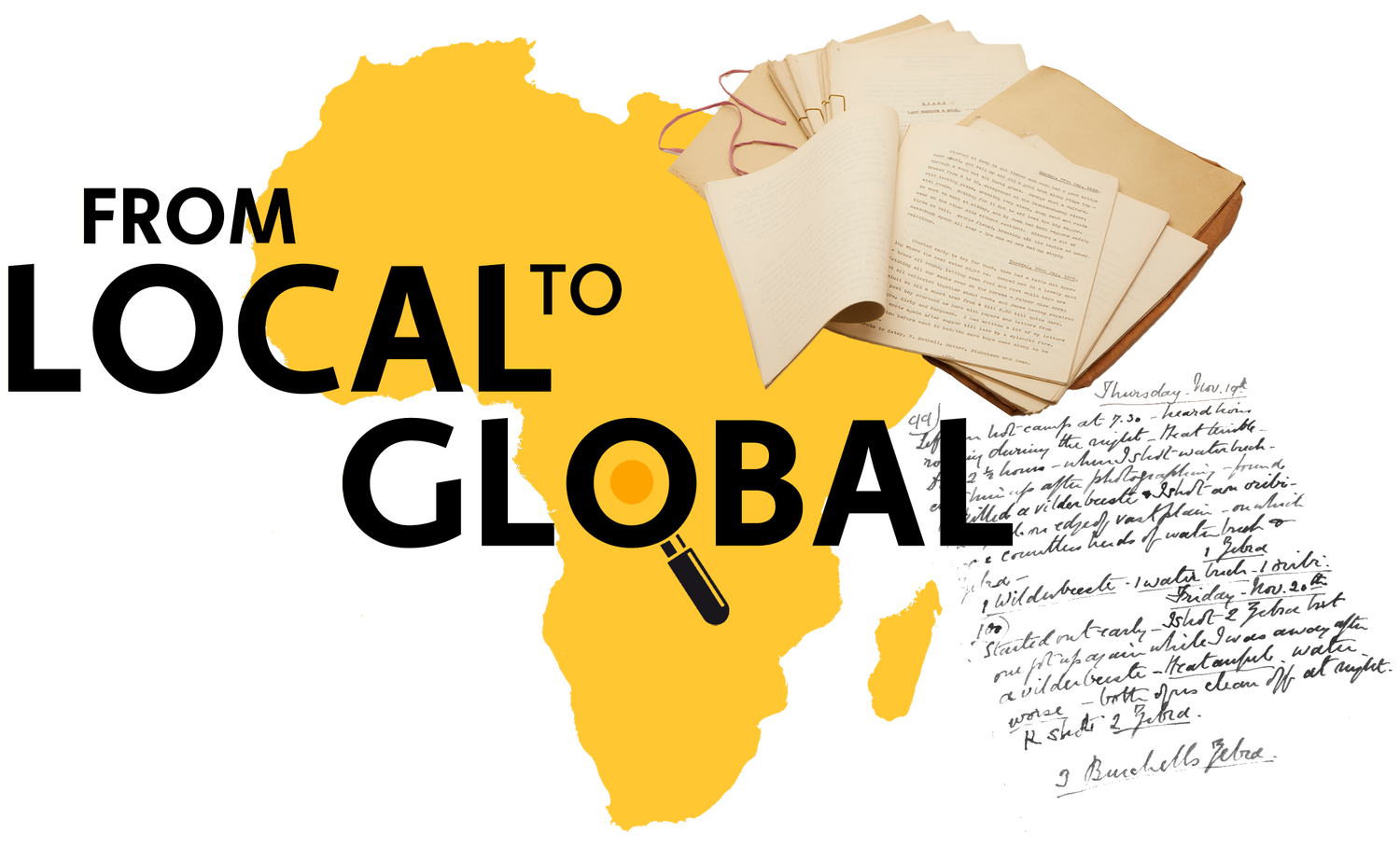

History of the Harrison Collection

By Gifty Burrows

Yorkshire Post, 13 July 1923

When Colonel James Jonathan Harrison died in 1923 his wife, Mary Stetson Harrison, was keen to donate his vast collection of glass plates, stuffed animal trophies, artefacts and documents to a public organisation for safekeeping. It would seem that Mrs Harrison had considered leaving the collection to South Kensington Museum but was not inclined to do so as there were conditions attached to it which she could not comply with [1].

There was some uncertainty as to where the Harrison collection should settle. Hull was also briefly considered before it found a home in Scarborough. At the time of the donation the Scarborough Library was managed by the Mechanics and Literary Institute, but they were in some financial difficulties.

Plans for the Public Library, 1928.The plans for the public Library from 1928. Prior to the opening as Scarborough first free public library the building had been the mechanics institute and the attached show the size of the building and the space for the Harrison Collection. © Scarborough Central Library

Yorkshire Post, 20 June 1930

There followed a period of further deliberation about whether the town should have a more substantial library and for it to be relocated but eventually its future was settled when the Scarborough Corporation was compelled to step in to manage the library in the same location. This was opened on 19th June 1930 by Sir Meredith Whittaker and it became Scarborough’s first free public library with the creation of the Harrison Room on the first floor to house the collection. The library itself stocked over 10,000 books[2] and was seen as the start of a bigger scheme,

There must have been considerable discussions behind the decision as it is interesting to realise that the opinion of Walter Harland was that placing the Harrison Collection in the library and banning ‘novels’ would maintain the ‘educational character’ of the building[3]. However, it was pointed out that such an act would remove authors such as Dickens, Scott and Shakespeare and would therefore place Scarborough in a disadvantage by making it less attractive as a recreational destination for residents and visitors.

© Scarborough Central Library

Leeds Mercury, 6 May 1924

At that time the size of the collection prevented the intended scientific arrangement being adopted and instead the collection was grouped into geographical regions such as South Africa, North America and Africa.

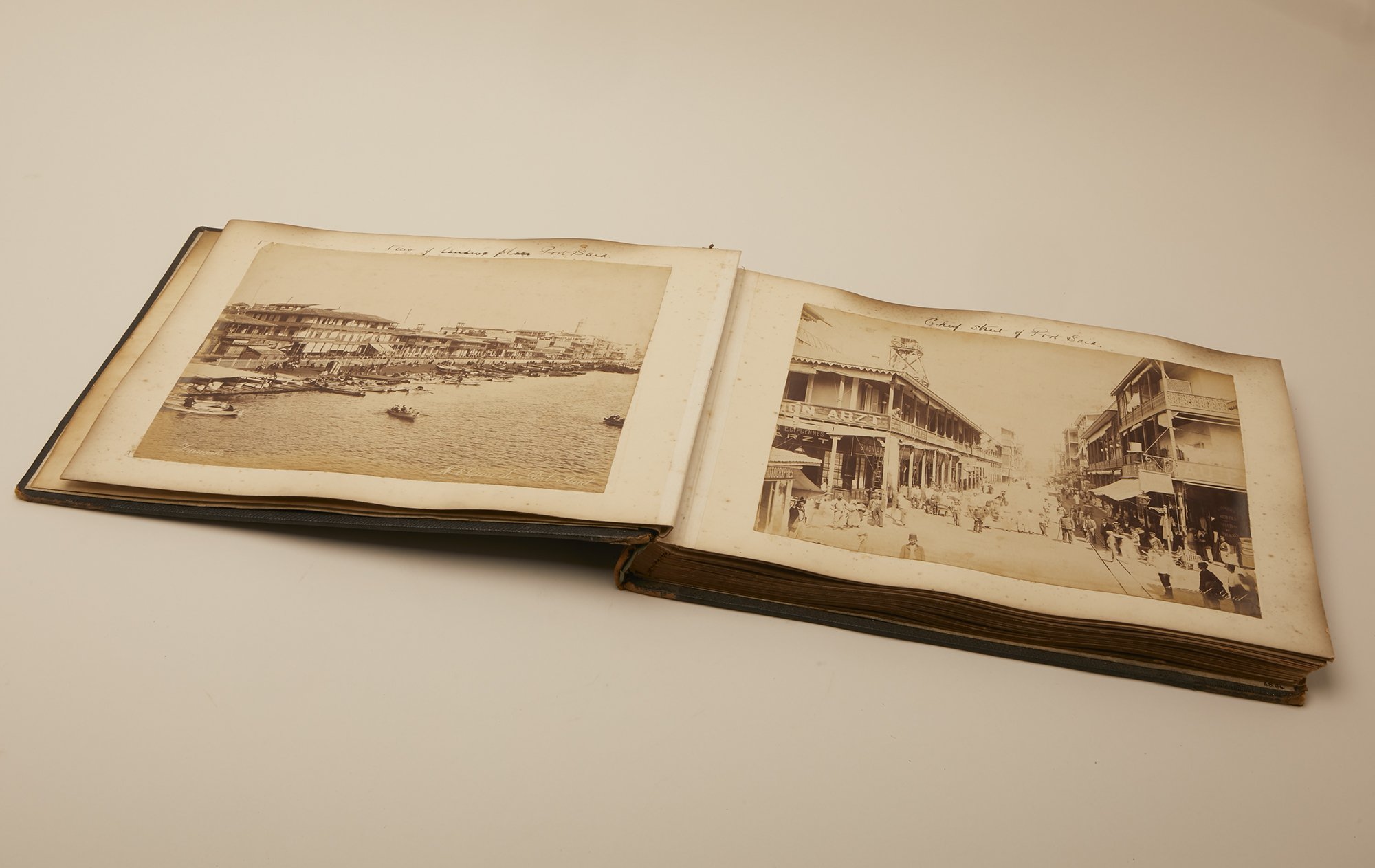

Visitors would have crossed a threshold flanked by a huge pair of bull elephant tusks and the room itself held a myriad of animals, birds, horns and artefacts on the walls and in glass cases.

Included in the African Section were larger specimens such as heads of a bull elephant, hippopotamus, rhinoceros, varieties of giraffes, buffalo, dwarf buffalos and antelopes. Specifically associated with the Belgian Congo was the self-attributed dwarf antelope, Neotragus (Hylarnus) Harrisoni which at the time was so rare that the Natural History Museum, South Kensington held the only other two specimens.

Other rare specimens (an attraction for trophy hunters) included the head of a Forest Hog, a whole Smaller Forest Antelope, a white thrush from Japan, a secretary bird from South Africa and even an extinct passenger pigeon.

Scale also held an attraction with large exhibits such as a moose, a giant Wapiti (elk) head with its 56 inch horns and a caribou which could be found in the North American section.

Stranger still, although the Harrison room had been established, it appears the intention was not to hold the collection there permanently as in May 1924, it was reported in the Leeds Mercury that Scarborough Corporation had made a decision to purchase Londesborough Lodge (later Woodend) and its grounds on the Crescent to house the Harrison collection[4]. The collection at that time was reported to be the largest of its kind in the world.

Letter From Sir George Sitwell to William Rowntree Regarding Woodend and the collections, 17th March 1934. © Scarborough Central Library

However, a letter from Sir George Sitwell to William Rowntree in 1934 showed that even at that time, a decision had not been made to definitely house the collection at Woodend. Opinion was still divided as is seen in Sitwell’s comments in expressing a preference for Woodend to become the town’s library rather than the venue to host the Harrison collection. These deliberations must have gone on for many more years because it was not until around 1951 that the collection was finally moved to Woodend [5].

After 15 years of the collection being installed in the Harrison Room of the library, in February 1945, Scarborough Town Council approved a change of use for the space with proposals to convert this substantial room and allow it to be used as a drama, music, film and lecture venue.[6]

Report of Scarborough Council Meeting, 10 February 1945 to discuss what was the future of the Harrison Room. © Scarborough Central Library

Image of Scarborough Library © Scarborough Central Library

This required considerable cost to make provision for heating, lighting and redecoration and the reason put forward for this change was a growing need from groups with an interest in the arts. Others felt that the move could allow the library to be extended, but essentially it demonstrated that it had not found a permanent home.

It is clear that the Harrison collection now held at Scarborough Museum is very different from that shown at Woodend Museum of Natural History.

This is how it was remembered by one visitor:

“One of my happiest memories of a childhood in 1960s Scarborough was weekly visits to Woodend, then the Museum of Natural History. My dad knew the curator, Ian Massie, and when I was only very young, we’d walk from our home nearby on Sunday mornings and, if I was lucky and Ian was around, he’d fish out one of the reptiles from the enclosure in the conservatory, now Woodend’s art gallery, for me to get a closer look at. But the highlight of those visits was always the big beasts, the lions and tigers and other exotic creatures and birds which I now know of as part of the Harrison Collection. They were overwhelmingly exciting for a small child.”

— Jeannie

However, by the 1990s the exhibits had been placed into storage and Andrew Clay who leads Scarborough Museums and Galleries recalls the following:

“My first acquaintance with the Harrison collection was in 2007, years before I become CEO of Scarborough Museums Trust (SMT). At that time, I had been recruited as the inaugural Director of Woodend, the former location of the Natural History Museum. When the building was being converted into the Creative Industries Centre, the contractors had to excavate any known voids. One such void existed under the room that now houses the SMT library. There was a bricked-up door overlooking Plantation Hill. When this doorway was opened a mass of decaying trophy heads spilled out on the grass bank. You can imagine the surprise of the workmen. The animal heads were part of the Harrison collection and had been hidden in this void for decades. They were in a rotten state and because they were contaminated with asbestos, had to be disposed of. One wonders why such lengths were taken to conceal them? Why weren’t they simply thrown away and thus eradicated from memory? Was there a guilty conscience at play, an attempt to hide an embarrassing episode in our history, maybe knowing one day, they would be re-discovered? We will never know…”

— Andrew Clay

We would like to acknowledge the assistance provided by our citizen researcher John Patrick and Scarborough Library.

References

Yorkshire Post, 13 July 1923, p. 6

Yorkshire Post 20 June 1930, p. 4

Letter from William Rowntree to Walter Harland, p. 2

Leeds Mercury, 6 May 1924, p. 13

Letter From Sir George Sitwell to William Rowntree 17 March 1934 p. 1

Scarborough Evening News, 10 February 1928</font>