Amuriape’s Daughter

By Dorcas Taylor

In Bedford, on the afternoon of Thursday 25 October 1906, Amuriape gave birth to a girl. The child was stillborn. Newspapers across the UK carried stories about the event, and it is from these that we can piece together information about the birth. A woman doctor, Dr Stacey, and a nurse from London, joined them in Bedford on Monday 22 October to oversee the birth. The group had been touring and on the Tuesday, two days away from the birth, Amuriape had been left in Bedford while the remaining five members of the group had moved on to appear on stage on the Wednesday and Thursday in nearby Luton.

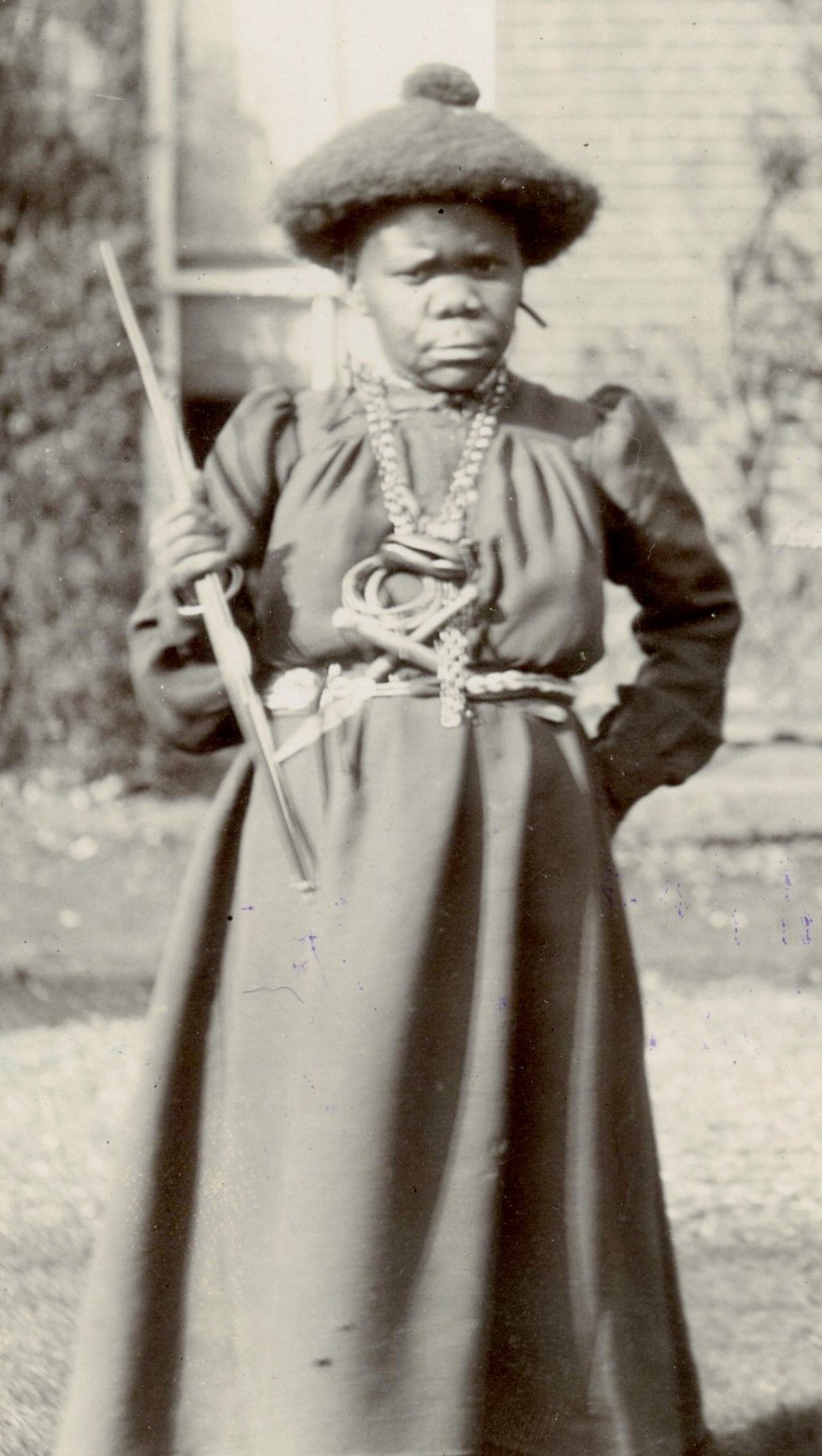

Amuriape in the grounds of Brandesburton © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

With the publicity that Harrison had generated around them, the Bambuti had been a national sensation since their arrival in England the previous year. The preparations for and reporting on the birth can be seen as another example of the way in which they were scrutinised and objectified by the British public [1]. That “the first pygmy baby ever seen in the whole wide stretch of the civilised world would be on view”,[2] suggests a British colonial mindset that saw the baby as public property. The papers had already reported that the child was to be named “the mighty atom”, a name better suited to a circus performer and likely to be based on her anticipated size. Nothing appears to indicate Amuriape had any involvement in the naming of her child.

The so-called ‘scientific interest’ in Amuriape’s baby was quickly noted in the press. “Medical associations and great doctors are to visit Bedford to see this pygmy baby”[3]. This is an echo of the way in which the medical profession viewed the Bambuti as specimens to be weighed and measured, much as when they first arrived in Cairo.

Reports note that the little girl, weighing 5¾ lbs, was “abnormally large”[4]. We can only speculate why this may have been the case. It could be possible that their diet in England had increased Amuriape’s weight and affected her health, which is often a factor in birth weights. We do not know whether it was one of the Bambuti or someone else who was the father as this is not mentioned in any reports. The newspapers viewed Amuriape’s age as one reason why her daughter may not have survived. Described as aged 33, 36, 38 in various press cuttings, it was suggested that her “advanced age for motherhood”, together with her “frail health” on arrival in England, had been a cause of “great anxiety”[5].

Amuriape in the grounds of Brandesburton © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

The baby is referred to in several newspapers as the “’Bedford-born’ British subject”[6]. Whilst, as with most newspapers then and now, this could simply reflect a proclivity for alliteration, it is curious that the baby is referred to as a British subject. In colonial terms, the child would have been a subject – a person living under colonial rule and subject to the authority of the colonising power – but not a British subject. Although the child had been born in England, her mother was a subject of King Leopold II of Belgium - he had deemed the Congo Free State as his personal property until it was handed over to the Belgian Government in 1908, whereupon it became the Belgian Congo. Amuriape was in England temporarily and with King Leopold’s permission, so it is more likely that the child would have shared her status.

We know nothing of Amuriape’s mental state during this tragic event. We learn of the “great disappointment” of “the mother, of Colonel Harrison, and of all connected with the troupe”[7], so her pain is seen on a par with Harrison’s and the other English personages, who had vested interests in the birth. No mention is made of the reaction to the news by the other Bambuti, nor how the child might have been mourned in a culturally appropriate way. There is no birth or death certificate and we do not know what happened to Amuriape’s baby. Shortly afterwards, Amuriape re-joined the group and continued ‘performing’ alongside them.

Stillbirths in the UK at this Period

By Janet Wilson

Babies who were stillborn in England and Wales during this time were not officially recorded. This did not happen until they were included in the Births and Deaths Registration Act of 1926, which came into force in 1927. In Scotland the registration of stillbirths did not become law until 1939.

Prior to this time if a child was stillborn then they could be buried without any form of medical certificate and it was common practice for medical staff not to complete any documentation about babies who were stillborn. It was frequently the case that bodies of stillborn children were buried in places other than cemeteries or burial grounds. Some cemeteries refused to bury stillborn infants in consecrated ground or if there was no certificate signed by a doctor or midwife so this limited where the baby could be buried [8].

Medical journals of the time drew attention to the remarkably unsatisfactory state of the law on this matter noting that it was a disgrace how easy it was to dispose of the body of a child by alleging they were stillborn. Before the act came into force there were questions raised regarding whether a child was stillborn or whether they lived for a short while before dying. There was evidence from articles in the British Medical Journal (1908) that children who died within 24hours of birth were received and buried as stillborn. If a child who had briefly lived after birth was regarded as being stillborn, this meant that their burial was ‘cheap and expeditious’ as it did not involve grave fees or funeral expenses. Pember-Reeves [9] records that mothers would have to find the ‘terrible sum’ of a pound to bury their child if it lived which was not required if it was stillborn. There are also examples of doctors offering to remove the body of a stillborn child to a hospital or university for pathological purposes. Other documents record stillborn babies being buried in mass graves or buried with a dead woman in the same coffin [10]. These burials contain no records of who the babies are and so it is not possible to trace and identify individual babies. It was common practice up until the 1970s in many hospitals for the stillborn baby to be taken away immediately after birth and for the parents not to be allowed to see their child. This was in the mistaken belief that the parents would be upset and traumatised by seeing their baby.

About the authors

Dorcas Taylor - is Curator of Special Projects at Scarborough Museums & Galleries, and lead for the From Local To Global project

Dr. Janet Wilson - is a Registered Nurse who has many years of clinical nursing experience and since 2004 has worked in Higher Education. She has a doctorate in Nursing and an interest in the history of healthcare practices as well as local history .

References

1. A short survey of media coverage about the baby’s birth includes the Luton Times and Advertiser; Luton Reporter; Dundee Evening Telegraph; Christchurch Times; English Lakes Visitor; The Bedfordshire Times and Independent; and even the Weekly Irish Times.

2. Luton Times and Advertiser, Friday 26 October 1906. The idea that Europe was ‘civilised’ and Africa was, in contrast, ‘uncivilised’ is the established colonial paradigm of the period.

3. Ibid.

4. Luton Reporter, Friday 2 November 1906

5. Ibid.

6. See, e.g. The Bedfordshire Times and Independent, Friday 2 November 1906.

7. Ibid.

8. Davis G. (2009) Stillbirth registration and perceptions of infant death 1900-1960: the Scottish case in national context. Economic History Review 62(3) 629-654

9. Pember-Reeves M. (1913) Round about a pound Little Brown Book group

10. Davis G. (2009) Stillbirth registration and perceptions of infant death 1900-1960: the Scottish case in national context. Economic History Review 62(3) 629-654